C.W. Gross is the writer of the blog Voyages Extraordinaires: Scientific Romances in a Bygone Age and has recently published the anthologies Science Fiction of America's Gilded Age and Science Fiction of Antebellum America.

On the Sublime and the Beautiful in Disney's Fantasia - Part Two

by C.W. Gross

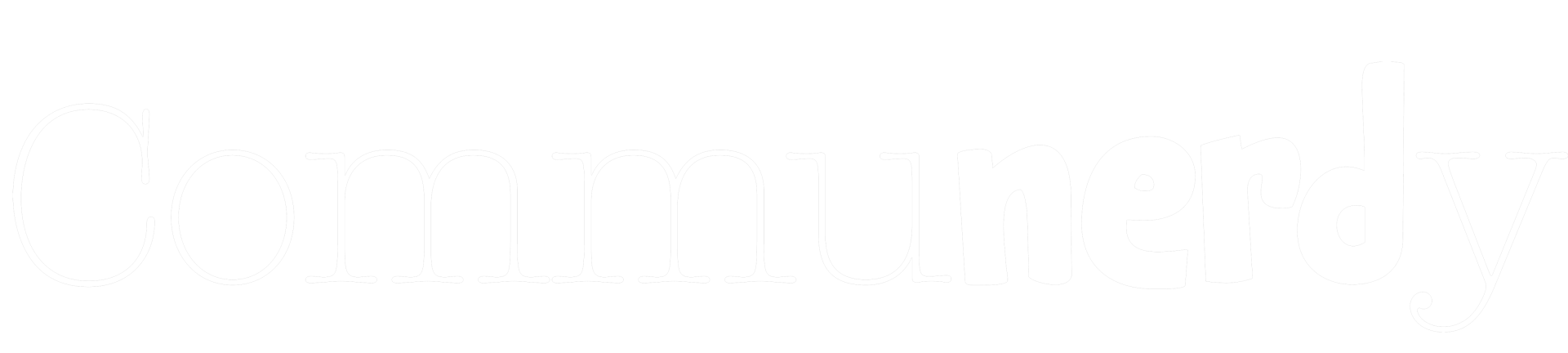

The Nutcracker Suite, Fantasia's second piece, has its cartoony caricatures (as caricatured as Tchaikovsky's music itself), but what is most remarkable is the delicacy of the faeries, dew, leaves, ice, and autumn seeds floating on the air. Making-of clips show how the semi-transparent seeds were painted, but I'm still astonished that it could be done. To achieve that delicacy and transparency on seed after seed, on cel after cel, is an unfathomable level of skill and patience.

Concept painting for The Nutcracker Suite. Photo © Disney

This piece foregoes the subject matter of Tchaikovsky's original ballet, which itself had a troubled history. Based on The Nutcracker and the Mouse King (1816) by Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann and Alexandre Dumas' 1844 adaptation, The Nutcracker debuted in St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892 to largely negative reviews. Many critics deemed it too chaotic, poorly paced, unfaithful to the original story, and with poor dancing from its cast of mostly children of the Imperial Ballet School. From the disaster, Tchaikovsky was able to tease out a 20-minute long Nutcracker Suite, Op. 71a. which did prove more successful. Productions of The Nutcracker ballet would not resume until 1919, in a new staging that resolved many of the original criticisms. By the time of Fantasia, however, The Nutcracker had largely fallen out of favour as a ballet. In the original narration, music scholar Deems Taylor acknowledged that it wasn't much performed anymore. The Nutcracker's rehabilitation came in the 1950's, when the New York City Ballet began its annual Christmas presentation of the ballet. It spread across the United States and Canada, becoming a seasonal fixture in ballet company schedules. Estimates put up to 40% of an average company's ticket sales being owed to The Nutcracker. Disney even gave it a sequel, of sorts, with the live-action Nutcracker and the Four Realms (2018), which has its references to Fantasia. Like many auteurs, Tchaikovsky was often ahead of his time. Maligned in its day, The Nutcracker is now the composer's most famous work.

Though not revolving around a human condemned by a curse to live as a Nutcracker, at war with the Mouse King until the curse is broken by a little girl on Christmas, Fantasia's Nutcracker Suite retains the character of a ballet. Fairies of spring, summer, autumn, and winter, of dew and frost and snow, glide along leaves and skate across water to the tones of the "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" and "Waltz of the Flowers." The various character dances of the Land of Sweets - Spanish chocolate, Arabian coffee, Chinese tea, Russian candy canes, etc. - are delivered by various plants and fish in imitation of their ethnic origin. Unlike later in the program - the satirical Dance of the Hours - this is a straightforward ballet that effectively captures the grace of that art form.

Concept painting from The Nutcracker Suite. Photo © Disney

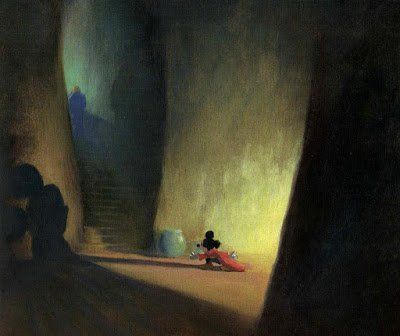

The Sorcerer's Apprentice: Romanticism and Expressionism

Fantasia's production began with The Sorcerer's Apprentice, the finished film's third piece. As originally conceived, the title role was to go to Dopey from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Echoes of his appearance and behaviour can even be seen in the final product. That role quickly fell to Disney's star performer, though. By the end of the Thirties, the spotlight was beginning to drift from Mickey Mouse and towards his more relatable compatriots Donald Duck and Goofy, who offered better slapstick laughs than could Mickey's good natured wholesomeness. Walt envisioned The Sorcerer's Apprentice as a spectacular "comeback" short on which no expense would be spared. Running into celebrity composer Leopold Stokowski, Walt broached the idea and was met with enthusiasm. But as costs on The Sorcerer's Apprentice soared, they realized that the only way to recoup their money was to go all-in on a theatrical feature film.

Set to the music of French composer Paul Dukas, The Sorcerer's Apprentice betrays its Germanic roots. The lair of the sorcerer Yen Sid could just as easily be in one of Fritz Lang's silent film epics, like Siegfried (1925). The use of shadow and construction of some of the shots recalls German Expressionist film. Very appropriate for a short based on a symphonic piece based on a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Concept painting of The Sorcerer's Apprentice. Photo © Disney

Itself based on a excerpt from Lucian's Philopseudes written in 150 CE, Goethe's Der Zauberlehrling, was a 14-stanza poem published in 1797. Goethe was a leading writer in German Romanticism, which was a literary, artistic, and musical movement that emphasized emotion, intuition, and imagination against the stifling Rationalism of the Enlightenment. He was no stranger to the subject of magicians dealing with powers beyond their control, having begun work on the classic Faust in 1772 and publishing an early version in 1790 (the complete play was published in two parts in 1828 and 1831). It seems natural that, as a Romantic writer, he would be concerned with the themes of calling up powerful subconscious forces that could escalate with unforeseen consequences.

A century after Goethe penned his words, French composer Paul Dukas wrote a symphonic tone poem inspired by it. Deems Taylor's narration was correct in stating that Dukas' piece followed a definite narrative, and Goethe's poem is traditionally published in the symphony programme. Such music is called "programmatic" in how it is intended to aurally illustrate a story. In this case, Dukas creates a soundtrack to Goethe's poem. Fantasia by its very nature, turns most of its pieces into programmatic music by adding animated vignettes along with them. The only major exception is the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, which Taylor identifies as "absolute music." He describes this antithesis to programmatic music as "music that exists simply for its own sake."

The Sorcerer's Apprentice is, sadly, Dukas' only lasting success. Other works like Ariane and Bluebeard are virtually unknown, a situation that was not helped by his very French act of having destroyed many of his own works later in his life. Not only that, but Mickey Mouse is the main reason for the longevity of that one piece. Orrin Howard of the Los Angeles Philharmonic bemoans Dukas' fate: "Pity the poor one-piece composer. Not the composer who writes only one piece, but the musical creator who enjoys far-reaching success with one of his works but is destined never to repeat that achievement with any other."

Concept painting of The Sorcerer's Apprentice. Photo ©Disney

On the Sublime and the Beautiful in Disney's Fantasia is a four-part series written by C.W. Gross. Part One can be found here, Part Three can be found here, and Part Four can be found here.