C.W. Gross is the writer of the blog Voyages Extraordinaires: Scientific Romances in a Bygone Age and has recently published the anthologies Science Fiction of America's Gilded Age and Science Fiction of Antebellum America.

On the Sublime and the Beautiful in Disney's Fantasia - Part Four

by C.W. Gross

The first recorded mention of Chernabog (also variously called Chernobog, Czernobog, Crnobog, and Tchernobog) was from a 12th century account of Slavic culture written by the German Christian priest and historian Helmold of Boseau. Born in Lower Saxony around 1120 CE, Helmold became a priest in 1156, after which he was asked to write the Chronica Slavorum, a history of the conversion of the Slavic people of modern-day Poland. Though ostensibly meant to shed positive light on the time between the conquests of Charlemagne and his own time (the book closes at 1171 CE), Helmold was rather critical of the Holy Roman Empire's actions against the Wends (another name for Polish Slavs). He decried the Wendish Crusades of 1147 and their leader Duke Henry the Lion as interested in only money and violence. Scholars generally see the Chronica Slavorum as being of questionable historical value where it predates Helmold, but fairly reliable where he is writing about contemporary events.

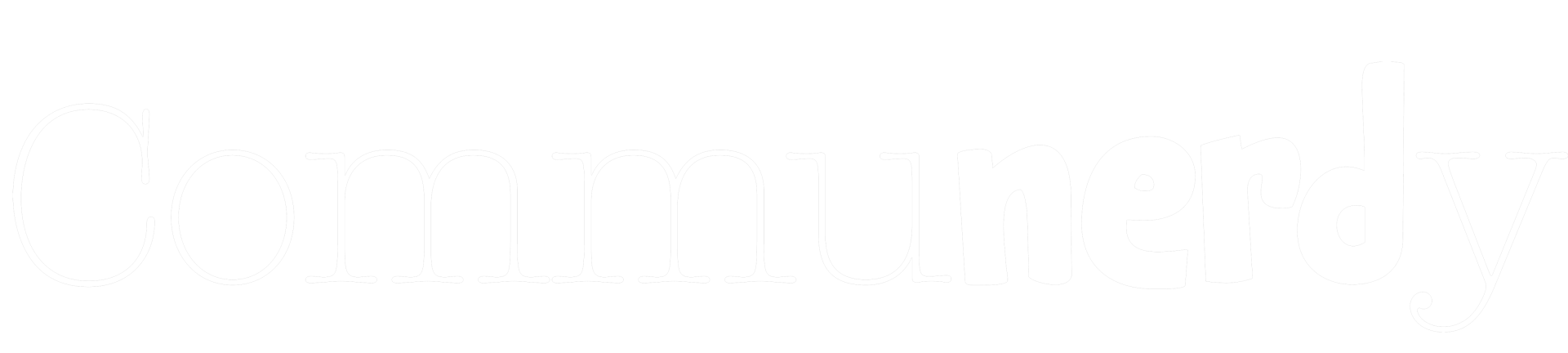

Concept painting of Night on Bald Mountain. Photo © Disney

A 1935 translation of the Chronica Slavorum by Francis Joseph Tschan gives us the following description of Slavic religious practice:

The Slavs, too, have a strange delusion. At their feasts and carousals they pass about a bowl over which they utter words, I should not say of consecration but of execration, in the name of the gods — of the good one, as well as of the bad one — professing that all propitious fortune is arranged by the good god, adverse, by the bad god. Hence, also, in their language they call the bad god Diabol, or Zcerneboch, that is, the black god.

"Diabol" derives from the Latin for Devil and is likely tipping us off to a Christianized interpretation of Chernabog and his relationship to the anonymous "good god." So far, amongst scholarly mythographers, there is no consensus on the identity of this "good god" or if the Wends were even dualistic in their polytheism. An interesting insight into the identity of Chernabog comes to us by analysis of Dazhbog. Whereas much about Slavic deities has been reconstructed by scholars, Dazhbog is well-known solar deity mentioned in several Mediaeval texts. What is curious about Dazhbog, whom was known to be worshipped across virtually all Slavic cultures, is that despite being a solar deity he was not uniformly regarded as good. A Serbian variation identifies him as a demonic entity who rules the underworld. His name also translates roughly to "dispenser of fortune": not necessarily good or evil, but the one who gives out both good and bad luck. With the arrival of Christianity, Dazhbog underwent a process of demonization, cast as an opponent to God. Nevertheless, looking at the example of Dazhbog, it is reasonable to consider that Chernabog may be both the "good god" and the "bad god." The ritual described by Helmold might not be an appeal to two different deities, but an affirmation of Chernabog’s dual nature as the giver of fortune, good and bad. This possibly being the case, and I admit that it is speculative, the Night on Bald Mountain and Ave Maria sequence of Fantasia may be giving us an accidental recapitulation of actual history. Chernabog - not necessarily a god of evil (or good) but certainly connected to the underworld and the dead - is supplanted by Christianity, which proceeds to cast him as the Devil.

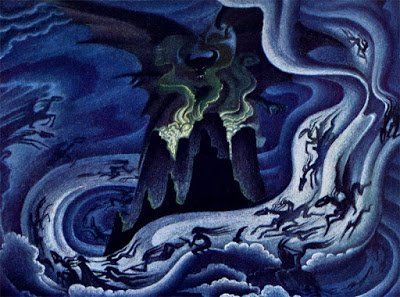

Concept painting of Night on Bald Mountain. Photo © Disney

It is generally assumed that the responsibility of identifying Disney’s monstrous entity with the ancient Slavic deity lies with Chernabog’s chief animator, Vladimir "Bill" Tytla. No name is given to the character in the film, and both production sketches and promotional materials of the time call him by all sorts of different, satanic names. Tytla, however, made use of the name "Chernobog" and was himself a Ukrainian-American who may have been familiar with the name through his ancestral roots. In his own words: "On all my animation I tried to do some research and look into the background of each character. But I could relate immediately to this character. Ukrainian folklore is based on Chernabog." Some linguists argue that the name of Chernabog is still in use, in a modified and nearly unrecognizable form, as a curse in Slavic tongues. While it’s not implausible that Tytla recalled his Ukrainian heritage, there is another very likely possibility: Chernabog is mentioned by name in the program of Night on Bald Mountain.

The history of Modest Mussorgsky's most famous work is circuitous, and the full piece was never heard during his lifetime. He first spoke of his intention to write an opera based on the story St. John’s Eve by Nikolai Gogol in 1858. Gogol's book, written in 1830, is a chilling tale of witches, greed, classism, and demonic possession. The date of St. John's Eve (June 24) is significant, as it marks Midsummer Eve, the summer solstice, and the Slavic pagan holy day of Kupala. There would be bonfires and ritual baths, young women would float wreaths in the rivers, and would-be couples would enter the forest together to find a rare (nonexistent) fern that flowered only on that night. With the arrival of Christianity, the date was claimed for St. John the Baptist and the rituals reinterpreted. However, folk memory retained the ancient pagan practices and began to see St. John’s Eve as a night of devilry and witchcraft.

That opera never materialized, but the composer did pen a tone poem called "St. John’s Eve on Bald Mountain" in 1867. Unfortunately, Mussorgsky's mentor condemned the finished work as "rubbish" and it went unheard until the 1930's. In 1872, Mussorgsky adapted "St. John’s Eve" for a collaborative opera-ballet entitled Mlada. This version was called the "Glorification of Chernobog," and features a ghoulish convention of ogres, spirits and demons. A young prince's betrothed was poisoned by a greedy woman and her father, who now wish his hand and his kingdom. She even goes so far as to sell her soul to the evil goddess Morena to achieve her goals, who hatches a plot to seduce the prince. The spirit of his betrothed leads the prince to the top of a bald mountain, expressing their mutual desire to be reunited in death, when the denizens of Hell tumble out of the underworld. Chief of them is Chernabog, who gives the prince a vision of Cleopatra in hopes that he will forget about his betrothed. It nearly works, but he is saved by the crowing of a rooster. Daybreak has come, and with it, the evil spirits disperse.

While Mussorgsky completed his contribution to the project, Mlada itself never was. The composer once more took his music and adapted it, this time as the intermezzo in an opera titled The Fair at Sorochyntsi. Sadly, this opera was left unfinished by Mussorgsky’s death in 1881. Friends of the composer, most notably Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, took on the task of adapting Mussorgsky's unfinished and unpublished works for public consumption. Utilizing "Dream Vision of the Peasant Lad," Rimsky-Korsakov created the version of Night on Bald Mountain best-known today. From Rimsky-Korsakov's program:

Subterranean sounds of unearthly voices. Appearance of the Spirits of Darkness, followed by that of Chernobog. Glorification of Chernobog and celebration of the Black Mass. Witches' Sabbath. At the height of the orgy, the bell of the little village church is heard from afar. The Spirits of Darkness are dispersed. Daybreak.

Both Fantasia’s conductor Leopold Stokowski (who in turn arranged Rimsky-Korsakov’s version for Fantasia) and its master of ceremonies, the music scholar Deems Taylor, would undoubtedly have been aware of this and perhaps it was they who suggested calling the character by that name. Rather than an inventive reinterpretation in the vein of the Pastoral Symphony or Rite of Spring, Night on Bald Mountain may be a fairly straightforward animating of the symphony's actual story.

However Disney’s most visually striking and viscerally powerful villainous figure got his name, it is certain that this name would have been largely forgotten if not for Fantasia. One of my fondest memories of Halloween was the annual ritual of watching Hans Conried as the Magic Mirror hosting an anthology episode of Disney villains, topped off with Chernabog’s leering visage chilling us to the bones before sending us out to scare up candy. Nevertheless, it would be a strange fascination to hold if there was not a deeper interpretation to draw from it. The complete Night on Bald Mountain and Ave Maria sequence goes beyond Good and Evil, as it were, to exemplify the difference between the Sublime and the Beautiful.

The best known meditation on the subject of the Sublime and Beautiful is by the English philosopher Edmund Burke, in his On the Sublime and the Beautiful. In this essay, he defines the Sublime as:

The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is astonishment: and astonishment is that state of the soul in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other, nor by consequence reason on that object which employs it. Hence arises the great power of the sublime, that, far from being produced by them, it anticipates our reasonings, and hurries us on by an irresistible force. Astonishment, as I have said, is the effect of the sublime in its highest degree; the inferior effects are admiration, reverence, and respect.

What affects this are such attributes as vastness, infinity, overwhelming and overarching power, privation, obscurity, darkness, magnitude, suddenness or shock, brash noise, and terror (each of which earns its own chapter in that captivating essay). Beauty, on the other hand, Burke defines as possessing the qualities of even proportion, delicacy, smoothness, mild colouration, softness in sound, grace and elegance, and so forth. Then to compare them:

For sublime objects are vast in their dimensions, beautiful ones comparatively small; beauty should be smooth and polished; the great, rugged and negligent: beauty should shun the right line, yet deviate from it insensibly; the great in many cases loves the right line; and when it deviates, it often makes a strong deviation: beauty should not be obscure; the great ought to be dark and gloomy: beauty should be light and delicate; the great ought to be solid, and even massive. They are indeed ideas of a very different nature, one being founded on pain, the other on pleasure…

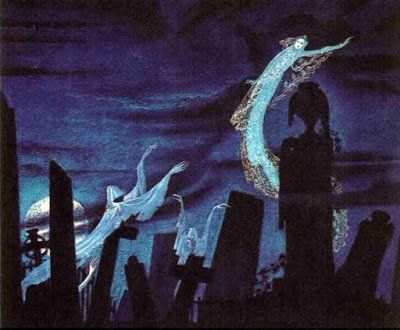

I do not think there is a more apt description of the contrasts between Fantasia’s bacchanal on Bald Mountain and the genteel melodies of processional monks. Chernabog, coherent with his origins as a dealer in good and bad fates, then represents Sublime forces contrasted against Divine Beauty. The battle between Good and Evil, between Chernabog's furious, destructive, sensual orgy of fire and the victorious monks' candlelit pilgrimage through a cathedral-like forest, is only the most superficial layer of interpretation. This isn't merely a moralizing metaphor for Evil's lively seductions and Good's pious serenity. It is a discourse on aesthetic philosophy and musical theory as a whole.

On the one side is the sublime of Night on Bald Mountain: everything grand, overpowering, horrifying, massive, ancient, dark, foreboding, the extremes of emotion, the ragged mountain, the crypts of the fallen warriors of battles long forgotten, cemeteries and ruin, of cacophony. On the other is the beauty of Ave Maria: everything delicate, sacred, soft, sensible, comforting, graceful, light, serene, of holy pilgrims, organic forms, and Schubert's great hymn set to a beaming dawn. Furthermore, Fantasia could be interpreted in its entirety as a meditation on these drives, from the beauty of fairies, magic, cherubs, and silly animals dancing ballet to the sublime of geologic cataclysms, prehistoric combat, wrathful deities, and alligators skulking under cover of darkness.

Concept painting of Ave Maria. Photo © Disney

Fantasia's Legacy

Pretty heady stuff, which is why I can understand that audiences weren't exactly looking for that kind of thing at that moment in history. While Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (my second favourite of Disney's animated films) was a milestone that broke all box office expectations, subsequent films suffered from diminishing returns. Pinocchio (1940) was more technically accomplished than Snow White, but lacked heart and the European market shut off by World War II. Fantasia bombed outright. The "Fantasound" surround sound system that Disney developed to achieve concert-real sound quality was expensive to install, the movie was expensive to make and Disney's most unusual and experimental to date, and the the US was on the verge of entering the war itself. Fantasia's returns were so dire that the film didn't start to recoup its production costs until its re-release in 1969!

The negative feedback and even more negative returns soured Walt to animation in the long term. He had built success upon success from Steamboat Willie to Silly Symphonies to Snow White, but Fantasia marked his first major failure. It wasn't just a missed shot either. Walt predicted that "'Fantasia' merely makes our other pictures look immature, and suggests for the first time what the future of the medium may well turn out to be." He felt that "This film is going to open this kind of music to a lot of people like myself who've walked out on this kind of stuff." It wasn't to be. The next film produced by his studio to turn a profit was Dumbo (1941), a fun, charming little picture that Walt generally had little to do with. The whole episode, also coinciding with the 1941 animators strike, was a blow to his confidence, sense of experimentation, and feelings of being vitally tapped into American culture. The receipts were in and there was nothing new, nothing higher, he could do with animation. After Fantasia, his own interests turned towards live-action, documentaries, television, and theme parks.

On the Sublime and the Beautiful in Disney's Fantasia is a four-part series written by C.W. Gross. Part One can be found here, Part Two can be found here, and Part Three can be found here.