C.W. Gross is the writer of the blog Voyages Extraordinaires: Scientific Romances in a Bygone Age and has recently published the anthologies Science Fiction of America's Gilded Age and Science Fiction of Antebellum America.

On the Sublime and the Beautiful in Disney's Fantasia - Part Three

by C.W. Gross

The first half of Fantasia is closed out with the ostensibly science-based Rite of Spring. Yet its evanescence of cosmic gas clouds is divine despite the scientific pretensions. I remember seeing this short in the second grade in the early Eighties, during our unit on dinosaurs, but it is certainly an artefact of its time. Regardless of the assistance of scientific luminaries like palaeontologists Barnum Brown and Roy Chapman Andrews, and astronomer Edwin Hubble, liberties are always taken when transmuting scientific ideas to film. Today, The Rite of Spring is enjoyable primarily for its art and its nostalgic image of prehistoric saurians.

Rite of Spring had the misfortune of being the only piece based on the work of a still-living composer. Igor Stravinsky debuted the original ballet on April 2, 1913, to a literally riotous reception. The two factions who enjoyed Parisian opera at the time - the bourgeoise in the boxes and the bohemian in the cheap seats - turned on each other and eventually the orchestra, with fists and chairs flying. The riot got such that the music could not be heard. Eventually the offending parties were ousted and the show could go on. What unfolded was a panorama of Russian pagan ceremonies re-enacted with the choreography of Vaslav Nijinsky and costumes and backdrops by Nicholas Roerich. Because it was so avant garde, reception of Rite of Spring was mixed. Conductor Pierre Monteux had to be coaxed into performing it, and years later recalled that no matter how much he sucked it up and did it, never never grew to like Rite of Spring. Scholars of classical music site that evening in 1913 as the one that changed everything for music in the 20th century.

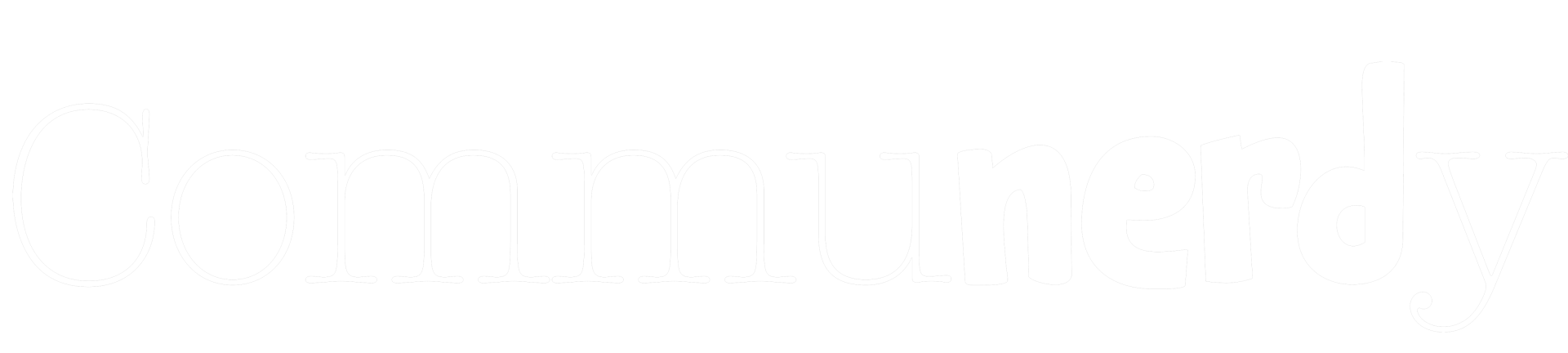

Concept painting of The Rite of Spring. Photo © Disney

Stravinsky's own reaction to Fantasia was conflicted. According to different accounts, he liked Disney's realization at the time, but grew a distaste for it. Stravinsky himself gave permission for Disney to use the piece, posed for photos with Walt, and gave no objections during production nor on the film's premiere. It was only much later in life that he decried it as "terrible" and an "imbecility." That much is a shame, considering what The Rite of Spring accomplished. Much of the segment is a study in special effects techniques more than traditional animation. The field of stars, molten Earth, billowing volcanoes, bubbling mudpits, and other artefacts of the Hadean Eon were rendered by innovative practical effects refined by the artist's palate. "Dinosaur movies" are a demanding, effects-intensive genre that beg for cinematic innovation. After the Hadean, Disney's animators depict a primitive, swampy world in deep, earthy tones. We've grown more accustomed since then to see colourful dinosaurs, very much like modern animals, in bright worlds much like our own (for example, in the BBC's Walking with Dinosaurs documentaries). These are dull, dim, archaic reptiles in an alien, reptilian, antediluvian world where everyone eats everyone else in a ceaseless and merciless evolutionary battle.

No wonder, then, that New York Herald Tribune reviewer Dorothy Thompson described Fantasia as "brutal and brutalizing," "an assault," "a performance of Satanic defilement," "so perverse an expression," an assault on "the civilized world," and an expression of Walt Disney's (Walt Disney's!) "sadistic, gloomy, fatalistic, pantheistic philosophy to record the Fall of Man and to record it with sadistic relish," a film in which "Nature is titanic; man is a moving lichen on the stone of time." Others rose to Disney's defence, decrying Thompson's column as "sheer, unadulterated hysteria" and "Philistinism pure and simple." Proving that it is not a new habit to call anything you don't like "Nazi," Thompson did exactly that to Fantasia: "All I could think to say of the 'experience' as I staggered out was that it was 'Nazi.' The word did not arise out of an obsession. Nazism is the abuse of power, the perverted betrayal of the best instincts, the genius of a race turned into black magical destruction, and so is the Fantasia." Carl Lindstrom, of the Hartford Times, decried "the Nazi cudgel" as "the most conscienceless thing that has occured to music in many a year," adding "It should be widely and deeply resented."

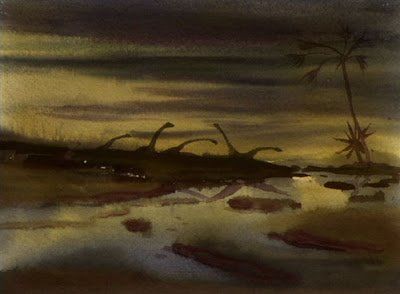

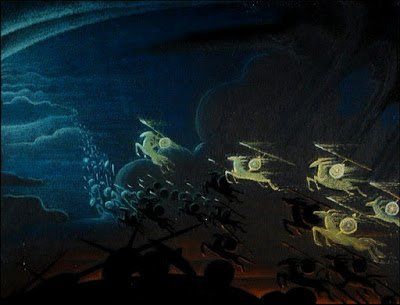

Intermission: The Fantasia That Could Have Been

Following Rite of Spring is a welcome intermission (something that these modern three-hour long films could benefit from) and an opportunity to discuss some of the ideas that did not make their way into Fantasia. As the film developed, Walt conceived of a rotating series of animated shorts to be switched out and remixed, adding vitality and longevity to the film. Rather than a mere theatrical film, Fantasia would have been a must-see theatrical concert event as it rolled through one's hometown every few years. Unfortunately, Fantasia was not a box office success and those plans were scuttled. Material still exists for a few of those intended shorts, like a dramatic rendering of Norse warfare to Richard Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries and Jean Sebelius' 1895 tone poem Swan of Tuonela, about a Finnish legend of a white swan that ferries the souls of the dead. Both pieces dealt with similar subject matter - the Valkyries ferried dead warriors to Valhalla - and mirrored aspects of Night on Bald Mountain, which did make it into the final film. There was also the problem of Wagner's popularity with the Third Reich in 1940. It would have been... impolitic... of Disney to have made that short at that time.

Concept painting of Swan of Tuonela. Photo © Disney

Concept painting of Ride of the Valkyries. Photo © Disney

The unused concept that came closest to completion was Clair de Lune by Claude Debussy. Actually, it did reach completion, but was pulled at the last minute in the interests of time. Debussy's classic piano piece, part of the Suite bergamasque written around 1890 and published in 1905, is visualized as a moonlight night on a bayou. After being cut, the animation was crudely reworked into the short Blue Bayou for the later Disney film Make Mine Music. After Fantasia's financial failure, Disney only revisited the format through popular music, which in the Forties meant Benny Goodman, the Andrews Sisters, and Roy Rogers. The main films in this format were Make Mine Music (1946) and Melody Time (1948). Some pieces from the two films could easily fit into Fantasia, like Peter and the Wolf, Trees and Bumble Boogie. The latter of these was another idea intended for Fantasia, using the original Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Flight of the Bumblebee. In Melody Time it is replaced by Freddy Martin's high-test Big Band version. Peter and the Wolf would have been far more engaging as an educational piece than the pedagogical "meet the soundtrack" segment that followed Fantasia's intermission. After these, we are ushered into the two most "Disneyesque" of Fantasia's pieces: The Pastoral Symphony and Dance of the Hours. These two most closely resemble the Silly Symphony cartoons of Disney's past, in which Fantasia itself is most clearly rooted.

The Pastoral Symphony and Dance of the Hours: Funny Animals

Having struck it big with Mickey Mouse in 1928, Walt sought a more challenging opportunity to develop the art form of animation. That pursuit manifested in 1929 with The Skeleton Dance, the first of the Silly Symphonies. In this peculiarly morbid short, a graveyard full of skeletons cavort to an original composition by studio musician Carl Stalling borrowing from Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns' Danse Macabre and Edvard Grieg's The March of the Trolls. The combination of animation with music proved a success and the Silly Symphonies henceforth became a format for both artistic and technical development. Flowers and Trees, released in 1932, was the first cartoon in Technicolor. The Three Little Pigs were introduced in the eponymous 1933 short, whose original theme song Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? would become a Depression Era anthem. Donald Duck debuted in 1934's The Wise Little Hen. Released the same year, The Goddess of Spring, retelling the story of Hades and Persephone, was Disney's first sustained attempt at realistically animating the human figure. Its inadequacies convinced Walt to rely on a process called "Rotoscoping" to achieve better results for his upcoming feature film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. In 1937, The Old Mill was the first short to make use of the multiplane camera, which added greater depth to animation, and to attempt more realistic depictions of animals and natural phenomena (once more in anticipation of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs released the same year). Finally, in 1939, after numerous Academy Awards, the series was brought to a close when feature films supplanted them as Disney's venue for experimentation and artistic excellence.

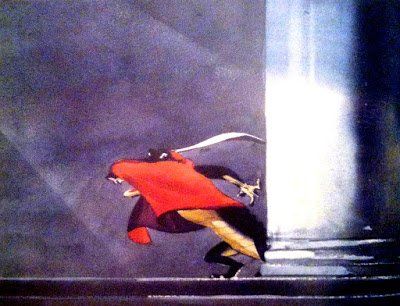

Yet many Silly Symphonies, like The Old Mill (based around excerpts from Johann Strauss II's The Gypsy Baron), could fit just as easily into Fantasia. Likewise, The Pastoral Symphony and Dance of the Hours could have been Silly Symphonies. The song Dance of the Hours, from Amilcare Ponchielli's 1876 opera La Gioconda, was in fact used for the 1929 Silly Symphony short Springtime. In Fantasia, this most famous of ballets becomes a satire of ballet itself, perhaps even leading to the original piece falling out of favour (Allan Sherman's Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh (A Letter from Camp) probably didn't help either). In Ponchielli's opera, a Grand Inquisitor has found his wife guilty of infidelity and forced her to drink poison, thus damning her soul by suicide. He reveals her dead body to his guests at the grisly climax of Dance of the Hours. In Fantasia, funny animals dance around! It's funny because the animals are fat! Get it?... Honestly, Dance of the Hours is the piece I can really do without (I would happily replace it with The Old Mill or Bumble Boogie), but Deems Taylor's totally straight introduction helps make it a bit funnier.

Concept painting of Dance of the Hours. Photo © Disney

Backtracking to The Pastoral Symphony, it may have been the most controversial piece in the film. There was the incident of a Topsy-like negro centaur handmaiden who has since been excised by editing and revised animation, but what remains is still a "Disneyfied" impression of Greek mythology. Many critics have perceived it as too cloying and childish, both with mythology and Beethoven's classic Romantic music. Dorothy Thompson, in her shotgun review, said that it alone should have been "sufficient to raise an army, if there is enough blood left in culture to defend itself", could have been used to torture Beethoven if he "had lived to see the inside of a Nazi concentration camp," and was, with the film as a whole, a "caricature of the Decline of the West." For those who like their Bacchus to be the spry embodiment of lustful indulgence rather than the squat embodiment of jovial excess, this sequence might be disappointing. To those offended by the debasement of Beethoven, I simply recommend to get over yourselves. For me, its rendering of Olympus and its Elysian Fields is paradisiacal, and the sequence of night falling and Artemis lighting the sky with her lunar bow is beyond compare in the canon of animation. There is genuine beauty amidst the cartoon centaurs.

Concept painting of The Pastoral Symphony. Photo © Disney

On the Sublime and the Beautiful in Disney's Fantasia is a four-part series written by C.W. Gross. Part One can be found here, Part Two can be found here, and Part Four can be found here.